This is the main conclusion of a survey of more than 114 participants aged between 23 and 74 from 22 different countries carrying out research in polar regions.

A new study led by the Institut de Ciències del Mar (ICM) in Barcelona has revealed that job precariousness and lack of opportunities in early and mid stages of the professional career, exacerbated during periods of crisis, are the main barriers that hinder research by young researchers in polar regions.

According to the paper, this is because, in these remote regions, fieldwork requires more international cooperation, extended planning horizons, large budgets and long-term investment, which are more difficult to secure and achieve during periods of austerity such as the recent and ongoing COVID-19 crisis. This crisis has led to the interruption of some scientific programmes collecting data for long time series that are now at risk of discontinuity, while some other shorter-term projects have already been postponed for at least two years already.

To carry out the study, recently published in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, researchers, many belonging to the Association of Polar Early Career Scientists (APECS), designed a survey that was answered by a total of 114 researchers aged between 23 and 74 years from 22 different countries who work in the polar regions.

Of these, 25% were predoctoral researchers, 55% were postdoctoral researchers and 20% were tenured researchers, which allowed the authors to assess the main barriers and success factors in polar research at all stages of the research career.

Barriers to polar research

The survey results reveal that the main barriers faced by polar researchers are at the institutional level. These include the fact that, during the early stages of a research career, most projects are of short duration, not providing any kind of security for researchers. In addition, burdensome administrative procedures and lack of opportunities, which are becoming more and more apparent in the global research world, deter many professionals from starting or continuing research careers.

On the other hand, according to the respondents, the main career success factor is personal experience, which they see as key to personal satisfaction and highlights the importance of good relationships with fellow researchers and supervisors. Networking and international mobility, which promote collaboration within the scientific community, are also key to professional success.

"The results of this analysis highlight the need for greater institutional support to promote leadership opportunities, networking, international mobility and awareness of job opportunities for polar academic researchers," states the ICM researcher and APECS member Blanca Figuerola, who led the study.

The researcher further highlights the need to raise awareness of socio-economic and gender inequalities existing in the research world, as well as to take practical measures to address them through, for example, initiatives that promote diversity such as Polar Pride and the availability of grants to cover publication costs for researchers in their early stages of research.

Peculiarities of polar research

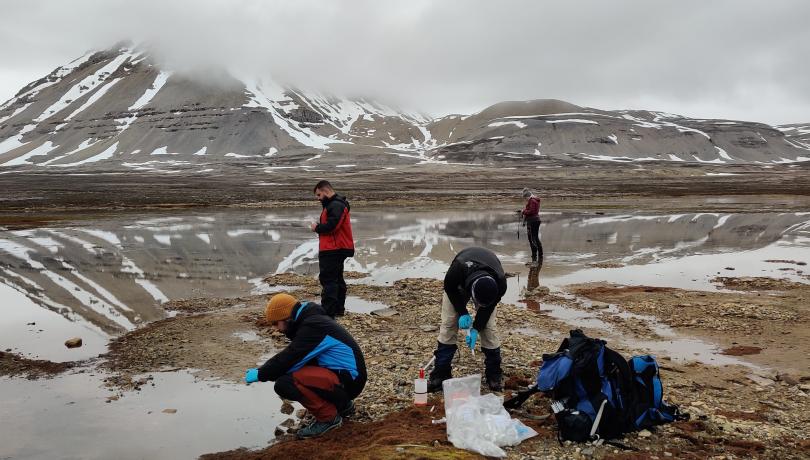

The results of this study highlight that research at the poles is not easy, although it is very necessary, as these regions are undergoing some of the most rapid environmental changes globally, and provide key information about the global climate and oceans that can help us to predict future changes and develop adaptation and mitigation strategies.

“The logistics needed to work in these regions is sophisticated, complex and expensive, and that most projects require significant long-term investment in human resources with specialized training and experience to operate safely”, highlights Luis R. Pertierra, co-author of the study currently engaged in a postdoctoral stint at the University of Pretoria in South Africa.

From his part, Peter Convey, co-author at the other end of his research career, with over 30 years’ polar research experience, highlights the very real and potentially career ending impacts of the loss of over two years’ research for late career scientists, combined with the loss of their key if often un-noticed mentoring and support role in the development of early and mid-career researchers.

For all this, the authors call for the creation of a more stable career structure to ensure the career security of highly trained personnel and maximise the return on the investment made for this purpose. Finally, they urge better supervision to enable them to become future leaders, and to ensure real opportunities for career progression at all stages of research careers.