An international team of researchers led by the ICM-CSIC has reconstructed the history of marine animal diversity from the Cambrian, some 540 million years ago, to the present day.

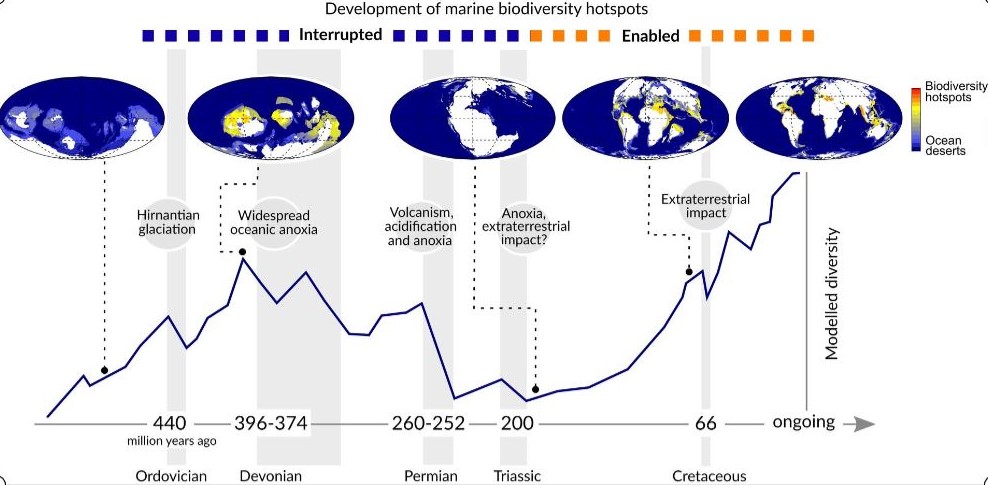

An international team of researchers led by the Institut de Ciències del Mar (ICM-CSIC) in Barcelona has developed a diversification model that makes it possible to reconstruct the history of marine animal diversity from the Cambrian explosion, some 540 million years ago, to the present day. The work, published today in the journal Nature, indicates that today's biodiversity is the result of long periods of environmental stability on Earth that allowed the development of biodiversity hotspots, regions with a high number of species.

The fossil record shows that life on our planet has been hit by at least five great mass extinctions over the past 500 million years. The mass extinction that occurred at the end of the Permian period, the largest of all time, wiped out more than 90% of marine species and brought ecosystems on the verge of collapse. Today, 250 million years later, life in the sea is more diverse than ever.

"The question is what happened so that biodiversity is greater today than ever," says the ICM-CSIC researcher and project leader Pedro Cermeño. "The problem is that the fossil record is incomplete, so to solve this question we needed to develop a new computational approach that allowed us to reconstruct the history of biodiversity. Our model is able to recreate the geographical distribution of diversity in today's oceans, especially the hotspots, and reveals the mechanisms that have created them," adds.

Researchers have found that the time between one mass extinction event and the next was key to allowing biodiversity hotspots to develop. "It was exciting to see that the pattern of global diversity resulting from our model of regional diversification was similar to that observed from the fossil record. This makes it relevant to use the model to reconstruct the spatial distributions of diversity in the past, allowing us to resolve when and how marine biodiversity hotspots originated," celebrates the ICM-CSIC researcher Carmen García-Comas, who has coordinated the study.

The limits of biodiversity

The new model also sheds light on one of the most controversial questions in evolutionary ecology: whether or not there is a limit to the global diversity that the Earth can support. Ecological theory states that as diversity increases and biological interactions, such as competition, intensify, the process of diversification slows to a halt. At this point, the emergence and establishment of a new species will inevitably lead to the extinction of an old one.

However, some scientists have argued that Earth's ecosystems are so heterogeneous that there will always be room for more species.

"Our results reconcile both views. While most of the oceans have levels of diversity well below their maximum, regions harbouring biodiversity hotspots may be close to their limit," notes Cermeño.

The team used a palaeogeographic model that tracks the movements of continents and the seafloor over millions of years, as well as an Earth system model that reconstructs the environmental conditions of ancient seas. Each tracked region accumulates diversity over time at a rate controlled by temperature and the amount of food available in each region at any given time.

"This modelling tool is very powerful because it allows us to explore many things, including what would have happened if some of the great mass extinctions had never happened, or if they had happened at another time in Earth's history," states the project leader.

Human interference in the natural functioning of Earth systems has prompted what experts call the sixth great mass extinction. According to the United Nations, as many species have disappeared in the last century as would have become extinct in 10,000 years assuming a normal scenario. In addition, 25% of the species evaluated by the International Union for Conservation of Nature are today in danger of extinction.

"This study shows that, if current trends continue, projected loss of biodiversity could take millions of years to recover, arguably beyond our own existence as a species," concludes Michael Benton, Professor at the University of Bristol and co-author of the paper.